Courtesy of Andrea Lavoie

Courtesy of Andrea Lavoie

© Tangotiger

Buy The Book from Amazon

See page below at Sports Illustrated (1984)

Don't Knock the Rock

By Ron Fimrite

Issue date: June 25, 1984

La Séance de Photographie was nothing more than just another Picture Day at the ball park, but in the extraordinary setting of Montreal's Olympic Stadium, a monument to unfulfilled ambition that has as its distinguishing architectural features an incomplete dome and a giant, crane, even the most humdrum event is transformed into something strange and unworldly. Picture Day, when camera-packing fans pile out of the stands to snap local heroes on the ball field, is pretty strange anyway. This is when the players become photographers' models, and most of the Expos looked as comfortable in that role as schoolboys on the principal's carpet.

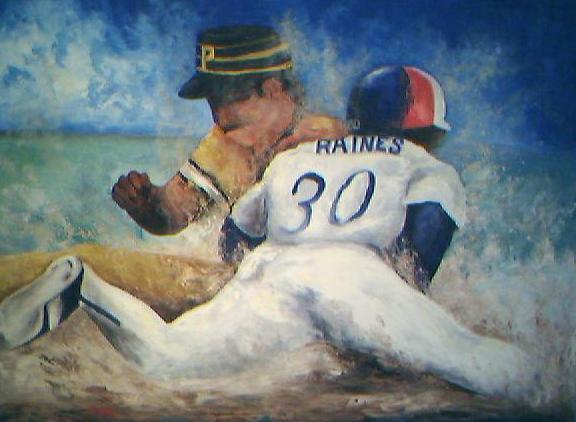

In fact, only one of the ballpayer-models seemed genuinely to be enjoying himself -- Tim Raines, the spunky outfielder. Raines clowned unashamedly through the entire 45-minute session, pretending to fall of his platform, hiding behind other players, putting his cap on backward, grappling with the Expos' resident creature, Youppi, who resembles a large orange platypus, and generally treating his photographers to a variety of imaginative poses. The fans responded in kind, cheering him and howling with laughter at his relentless japery. He made the whole bizarre spectacle seem fun. Raines can do that to a ball game, too. He plays with such unbridled exuberance that he can make a dull game exciting, particularly when he is dancing off first base preparing to plunder second. He has a keen sense of showmanship. "Stealing bases," he says, "can be as exciting as hitting home runs. The fans come out to the park to see people like Rickey Henderson, Willie Wilson and me." In only his fourth season, Raines has become one of the game's most colorful players, as well as one of its best. "He's such a pleasant, effervescent, lovely guy," says Expos president John McHale. "And he can play like hell."

That he can. Raines is the first player since the White Sox' Luis Aparicio in 1956, '57 and '58 to lead his league in stolen bases in each of his first three seasons. As a rookie in the strike-shortened 1981 season, Raines stole an astonishing 71 bases in 88 games. Last year he stole 90, and this year he has yet to be caught in 22 attempts and has a string of 31 successful steals dating to last Sept. 22. On the basis of a minimum of 300 attempts, Raines now has the top career percentage for steals, .867, in baseball history.

"I try to get as much of a lead as I can without having to dive back to the base," says Raines. "For me, that's one foot on the turf and one on the dirt. I rely on jumps and quickness. I'm at top speed after one step. You have to have acceleration to be a base stealer. If you have all of that, it takes a perfect throw."

But base running is just one aspect of a brilliant overall game. Raines, a switch hitter, batted .298 last year, scored a league-leading 133 runs and hit 32 doubles, eight triples and 11 homers, including two grand slams. Batting leadoff, he drove in 71 runs to become only the fifth player in history, and the first since Ty Cobb in 1915, to steal more than 70 bases and drive in more than 70 runs in a year.

On defense Raines led all National League outfielders in '83 with 21 assists, and he tied a team record by making only four errors. He has been shifted from left to centerfield this year to take greater advantage of his sprinter's speed and to give former centerfielder Dawson's aching knees some relief in right. Expos coach Felipe Alou, who played alongside Willie Mays with the Giants and therefore knows a little about the position, says of Raines, "I think he'll wind up as the best centerfielder in the game. He may not have Mays's or Dawson's arm, but he has great range, and with his speed he can play shallow. He gets a good jump on the ball, and he's not bothered by walls. He has a great sense of where he is on the field. Mays had that. You'd think Willie would kill himself running into a wall, but he never did." Manager Bill Virdon, himself a premier centerfielder in the '50s and '60s, says Raines has "the three ingredients you need to be a centerfielder -- judgment, speed and good hands. And he covers so much ground, he was wasted in leftfield."

Teammate Pete Rose is unequivocal in assessing Raines: "Right now he's the best player in the National League. Mike Schmidt is a tremendous player and so are Dale Murphy and Andre Dawson, but Rock [Raines's nickname, more about that later] can beat you in more ways than any other player in the league. He can beat you with his glove, his speed and his hitting from either side of the plate. And he has the perfect disposition for a great player -- he has fun. He's just a happy guy. You can't tell if he has gone oh for four or four for four. He's the same at eight in the morning as he is at eight at night. I've never seen him in a bad mood. And as far as running the bases, I don't see how they ever throw him out. But he doesn't just do it on speed alone. He knows the pitchers, so he gets a great jump."

"If anyone ever had million-dollar legs," says the veteran infielder Chris Speier, "Timmy's got 'em."

Raines drove in so many runs leading off last season and hit so well with runners in scoring position -- a team-leading .368 -- that Virdon dropped him from leadoff to third in the batting order this season, a controversial move that some observers felt would both change and hurt Raines's game. Well, they were wrong and they were right. At the end of last week Raines ranked among the league's top 10 players in on-base percentage (.396), hits (73), runs (41), RBIs (37), walsk (37) and, of course, steals, but his average was down to .300 from a high of .344 on May 14. Because of that dip, Virdon returned him to the No. 1 position June 11. "We moved him because he was struggling and we were struggling," says Virdon. "We thought we'd give him back a role he was more familiar with, but I still think he can be a good number three hitter. He doesn't go for bad pitches and that's important in batting third. We will try it again."

Raines, typically, doesn't care where he plays or bats, although he was worried at first that the move to center might offend Dawson, a fellow Floridian who is his closest friend on the team and the godfather and namesake of his younger son. "We had the best centerfielder in baseball out there in Andre," says Raines. "He's helped me so much. He's helped my career just by being around him. He's been like a father as well as a teammate and a friend to me. But he figured it was a good move for him, especially the way his knees felt. Now we joke about my legs going bad in centerfield. Actually, I think playing center is easier. Everything is in front of you and most of the time the ball comes straight without those slices you get in left and right. And there's more room to work with out there. Anyway, I've been here four years and played three different positions -- second, left and center. Second isn't my position, though. There was no way I could catch a ground ball hit right at me. I guess that's how I got the nickname Rock. I got it my rookie year -- they say because of my hands, but I like to think it's more because I'm short [5' 8"] and stocky [177 pounds]. You know, built like a little rock.

"As far as hitting first or third is concerned, I know now I can hit from either spot and be comfortable. The first month and a half I was hitting near .350, but then I went into a slump and it was time for a change. There certainly is a difference in the two spots. I'm seeing a lot better pitches, more fastballs, at leadoff. But Virdon says he's going to use me in both spots, and I like that."

Just 24 years old and approaching the top of his form, Raines has an enviable future. "He's got so many years ahead of him," says catcher Gary Carter, "that I see no reason why he can't be in the 3,000-hit club." "Only an unforeseeable injury can keep him from greatness," says pitcher Steve Rogers. "I think Rock has more potential than Joe Morgan," says Rose. What a future, indeed. And yet, not quite two years ago, Raines didn't seem to have any future at all, except as a cocaine addict. After his magnificent rookie season, he tapered off perceptibly in '82. He was scarcely a washout, hitting .277 and stealing 78 bases; a player with his talent can survive for a time on natural ability alone. But there were ominous signs that not all was well with him. "We suddenly saw him not running when he should have and holding onto the ball when he should be throwing," says McHale. "He would miss practice or not be on time. That was just not Tim Raines."

On June 29 of that year, Raines didn't appear for a game against the Mets, complaining of a headache and nausea. McHale sent team physician Dr. Robert Broderick to Raines's apartment in downtown Montreal. "The doctor said he was in dangerous condition and needed help immediately," says McHale. It was discovered that Raines had a cocaine habit; ultimately cocaine would cost him $40,000 in the first nine months of '82. It was apparent he needed more help than the psychiatric care the Expos could provide him. The '82 season ended on Sunday, Oct. 3, and on Thursday he entered the CareUnit Hospital in Orange, Calif. He stayed a month and was joined for his final week by his wife, Virginia, and his parents, Ned and Florence Raines of Sanford, Fla. "We'd have these group rap sessions," says Florence. "I'd be there listening to total strangers, and tears would be running down my face."

"I realized how much my career and my family meant to me," recalls Raines, who says he has not used drugs since. "I was in danger of losing both."

"It was murder on me," says Virginia. "I thought I needed a psychiatrist. I didn't know who to turn to. I just prayed it would stop. Now, I thank God."

"I couldn't figure out what was happening to him," says Ned. "He sort of kept that problem hid. He'd miss games, and I'd ask him what the matter was, and he'd just say he was tired, not feeling good."

"It knocked me off my feet," says Florence. "I had no inkling at all. Tim was always the kind of kid who didn't talk much. But he was never any trouble. Not a mean bone in his body. I'm just glad he had the sense to get help before it took control of him. You do what it tells you. I'm glad he couldn't handle it. That made him realize the danger."

"I feel I've gained from the experience," says Raines. "I'd rather it never occurred, but now that it has, it's a blessing it happened to me when I was so young. I was just trying to keep up with the night life, I guess. I was just a kid from a small town. It was an experience I tried, but I couldn't control it. It's made me bear down a lot harder since. I hope my play has made a lot of people forget about it. It's just a load off my back, and now that it's over, it's over."

Raines and his teammates realize he will have to work to make certain it is, in fact, over. "The maintenance of sobriety should be the most important thing in his life now," says Speier. "When you've completely pushed your emotional maturity back with drugs, and then the real world suddently hits you in the face, it must be like going through adolescence all over again at 24. I'd say he's handled it well." Dawson says, "I can't say I counsel him, but I want him to know if there is anything on his mind, I'm there to talk."

Raines was born and reared in Sanford, a town of about 20,000 in central Florida, not quite an hour's drive northeast of Orlando. "It's claim to fame," he says, "is that the auto train goes through there. You put your car on a special part of the train and go with it where you want. I've never ridden it." His father, who has worked for the same construction company for 26 years and lived in the same house for 23, played semipro baseball for the Sanford Giants until he was 34 (he's 47 now). "I hurt my shoulder playing and had to miss work a few days," he says. "I had bills to pay. I couldn't afford to be off the job."

The senior Raineses live in the green three-bedroom clapboard house on Airport Boulevard that Tim grew up in. There were seven children in all. The youngest, Anita Gail, was killed by a car right outside the house when she was four years old. "She'd be 20 now," says Ned Raines. "The driver went right into that oak tree out there." Two of Time's four brothers played minor league baseball -- Levi, 28, with the Twins' organization and Ned III, 25, with the Giants. In one local all-star game, four Raines brothers formed the infield -- Levi at first, Sam, now 23, at second, Ned at third and Time at short. The oldest, Tommy, now 30, missed this historic occasion.

It was a close family and a highly competitive one. All of the males were fast on their feet."We'd race against Pop as kids until somebody beat him," says Tim. "I was the first to do it. I was 15. I think Levi was the number one athlete in the family, though. He set high standards for the rest of us. We were a middle-class family. All the boys slept in one room -- we had bunk beds -- and our sister, Patricia, now 27, had a room of her own. She had it made. We seemed to always get along. Our ages were so close that we were together a long time. Ned III played baseball and football with me in high school. We were co-MVPs on the Seminole High baseball team one year, and in football I was the tailback and he was the fullback. He blocked and I ran the ball."

Father Ned is built like son Tim -- short and muscular. He also has his son's gentle nature and easy laugh. "You know I was telling a lot of people back then that I thought my boy Ned would be in the big leagues before Tim," he said recently, reminiscing while barbecuing ribs in his backyard. "Ned could hit the ball farther, and he could field good. He had all the potential. Well, I bet the coach at Seminole High that Ned would make it first. No money, understand, just a dinner bet. I think Ned just got a bad break with the Giants, and then all of a sudden, Time made it. That coach was right there demanding his dinner."

Virginia Hilton, who was soon to be Tim's wife, was a year behind him in school. She played clarinet for the Seminole marching band when Tim was starring on the football team. "I enjoyed playing in the band," she says, "but then somebody broke into the music room one night and stole my clarinet. That was the end of my music career, so I turned to sports. That's where I really got to know Tim. We'd run on the track together. I figured if I ran with him it would help me get faster because I'd have to push myself." Only 5' 2", Virginia pushed herself to an 11.1 100, and for a time she was the school record holder at that distance. Tim, running in track meets only on days when there were no baseball games, ran a 9.7 100 and a 41 flat in the 330 hurdles the very first time he competed in that event. He also long jumped 23' 2".

But football was his sport in high school. In his senior year he scored 18 touchdowns and averaged 10.5 yards a carry in leading Seminole to an undefeated season. Alas, one of the Seminole players was declared scholastically ineligible so two games were forfeited, and the team didn't make it to the state championship playoffs. "The whole school was just devastated," says Tim. "It was like a cloud had passed over it. But maybe it was a blessing in disguise. I might have gone on to play football."

Instead he signed with the Expos after graduation in 1977, married Virginia in '79 and is now the father of Tim Jr. (Little Rock), 4, and Andre (Little Hawk), who will have his first birthday on July 10. "It's all happened so fast," says Virginia. "When we were first married, we didn't have a place to live. Now we've got two. I don't know about this superstar stuff for me and the kids, though. We might have to stay inside and let him go out where all the people are. But if it takes that to keep him happy, then that's what it will be."

Tim was finishing lunch in a Montreal café on a rainy Saturday. He stirred his coffee gently and smiled. He had just told the story of his drug addiction for the umpteenth time, and he felt relieved to have that out of the way. Rosier times lay ahead. He laughed. "I never dreamed of playing major league baseball," he said finally. "I have to pinch myself to make certain it's real because I'm afraid I'll wake up and find myself back in Sanford. Yes, things are looking up. I just hope I never have to look back."

Issue date: June 25, 1984